Java Threads

Reference: JavaGuide

Threads

Thread Implementation

A Java program runs as a process and is actually multi-threaded concurrently; the main function is the main thread. Each instance of java.lang.Thread that has called start() and not yet finished is a thread. Java threads are the concurrent execution units of Java programs.

One-to-One Thread Model✨

Each Java thread corresponds to a kernel thread in the operating system, fully utilizing multi-core processors. (Now Windows and Linux use this.)

JVM implements Java thread creation and synchronization by calling the thread library provided by the OS; Java thread scheduling and management are handled by the OS.

Many-to-One Thread Model

What are user threads? They are threads fully implemented in user space; the OS kernel is unaware of them. User thread creation, synchronization, destruction, and scheduling are all done in user mode without kernel help. If implemented well, these threads don’t need to switch to kernel mode, so operations are fast and low-cost, supporting larger numbers of threads. Some high-performance databases use user threads for multi-threading.

Multiple user threads map to one kernel thread. Thread switching is very fast and can support many user threads. But cannot utilize multi-core processors; blocking operations can hang the entire process.

Java used this early on.

Many-to-Many Thread Model

Multiple user threads map to a few kernel threads. Implementation is complex. Goroutines use this model.

Creating Threads

Strictly speaking, the only way to create a new thread in Java is the start() method.

Inherit Thread Class

Override the run() method of Thread class.

| |

Implement Runnable Interface

Pass the implemented class object as parameter to Thread constructor.

| |

Runnable interface is more flexible, allows better resource sharing (multiple threads can share one Runnable object), and works better with thread pool APIs.

FutureTask

Can return task execution result.

| |

Can I call Thread’s run() directly?

If you create a thread and call thread.run() in main, it’s still the main thread executing run()’s logic.

Calling thread.start() starts a new thread, puts it in RUNNABLE state, and hands run()’s logic to the new thread.

Thread Lifecycle and States

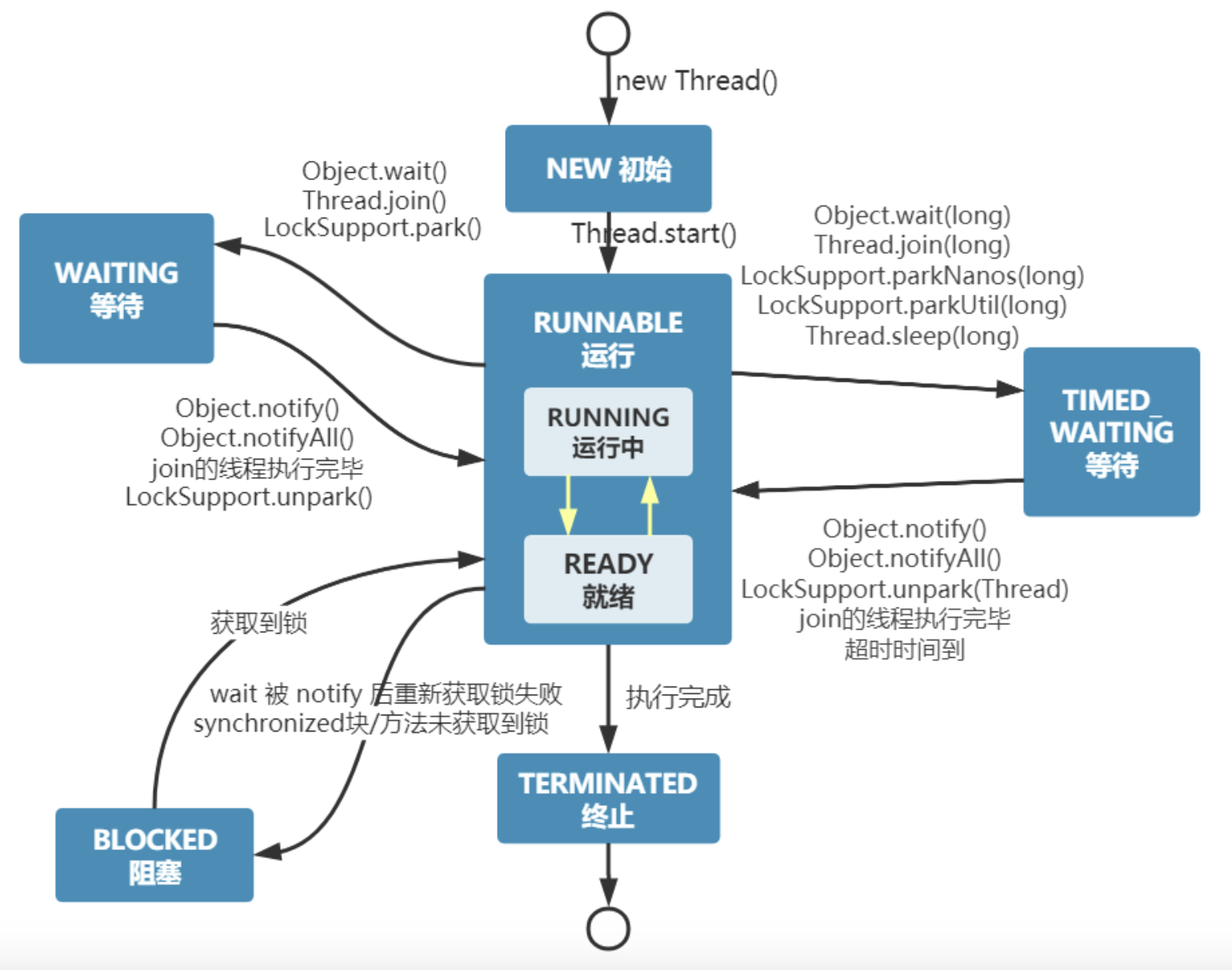

Java threads have six states.

- NEW, initial state after creation

- RUNNABLE, state after start(), includes OS thread READY and RUNNING. Either waiting for OS scheduling or running.

- WAITING, thread won’t be scheduled until explicitly woken by another thread.

- TIMED_WAITING, thread won’t be scheduled, woken by system after time.

- BLOCKED, blocked without lock, until another thread releases lock; JVM randomly picks or sequentially chooses a BLOCKED thread for the lock.

- TERMINATED, thread has finished execution.

Why not distinguish READY and RUNNING? Because time slices switch quickly; a thread might execute briefly then schedule to others.

sleep() and wait()

sleep()

Thread.sleep(2000); // Sleep thread for 2 seconds

sleep() is Thread’s static native method, changes thread from RUNNABLE to TIMED_WAITING. Does not release lock.

wait()

wait() is Object’s instance native method, must be called in synchronized block/method, releases lock.

| |

wait() changes thread from RUNNABLE to WAITING, enters object’s waiting set.

Another thread on same lock calls lock.notify(), randomly wakes one from waiting set, adds to entry set (sync queue), state from (TIMED) WAIT to BLOCKED.

Sync queue: When thread wants synchronized lock but doesn’t get it, adds to lock’s sync queue, state BLOCKED. When lock released, JVM randomly (unfair) chooses thread to grant lock.

wait() must be instance method because releasing lock operates on the lock object.

Multi-Threading

Java Thread Scheduling

Scheduling types: Cooperative and Preemptive.

Cooperative: Thread controls its execution time. After work, notifies system to switch. Advantage: No sync issues. Disadvantage: One thread running too long blocks others.

Preemptive: System controls execution time.

Java provides 10 thread priorities; if two RUNNABLE, higher priority scheduled first. Java threads map one-to-one to kernel threads, Java priorities partially correspond to kernel priorities.

Single-Core CPU Running Multi-Threads

Threads are CPU-intensive or IO-intensive. For CPU-intensive, frequent context switches reduce efficiency; for IO-intensive, switching during IO wait allows others to work, reasonable.

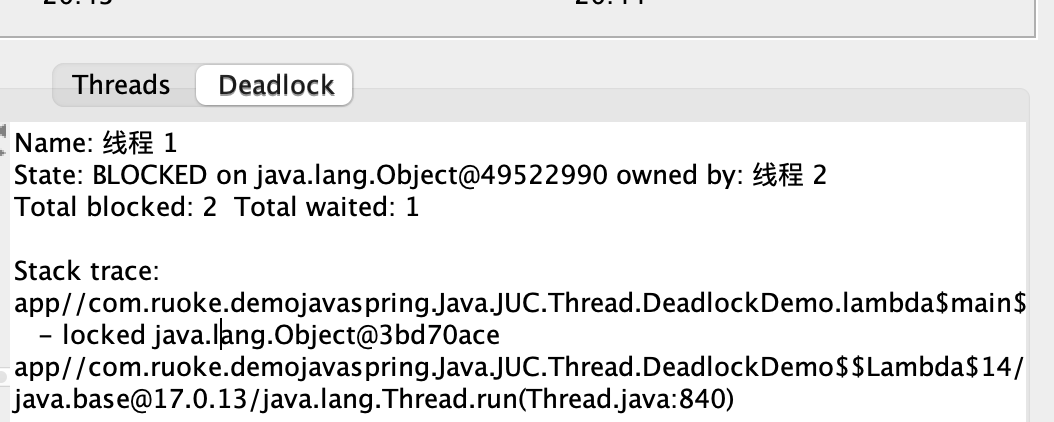

Deadlock

Deadlock conditions: mutual exclusion, hold and wait, no preemption, circular wait

| |

Run jconsole, select process, view threads